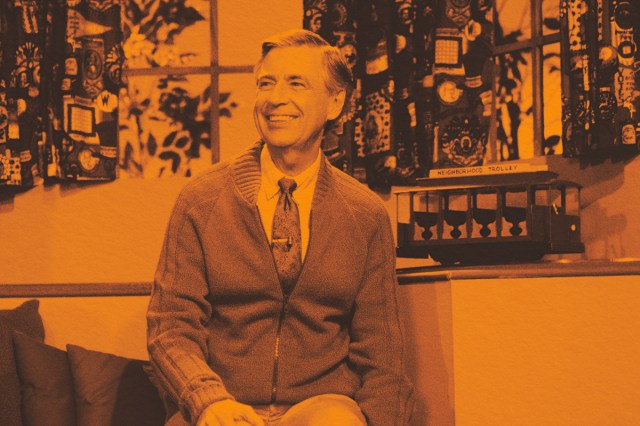

“Won’t You Be My Neighbor” was the cheerful theme song of the long-running TV show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, sung by none other than Fred Rogers himself. This friendly tune is easy to sing along with, but imagine how it would sound if the contraction “won’t” were replaced with “willn’t.” If it followed the usual pattern for contractions, “will not” should become “willn’t.” But of course, we use “won’t.” How did that happen? Centuries of language evolution are to thank for this unique contraction.

Most standard English contractions follow one of three patterns: drop the first letter of the second word (“I’m,” “they’re,” “how’s”), drop the second letter of the second word (“shouldn’t,” “don’t,” “isn’t”), or drop the first two letters of the second word (“it’ll,” “he’ll”). “Won’t” appears to follow the second rule by dropping the “o” in “not,” but there’s something unusual about it. Unlike with “don’t” (“do not”) or “isn’t” (“is not”), the first part of “won’t” doesn’t clearly come from the first word (in this case, “will”). So, why not just say “willn’t”?

The answer lies in a rather messy evolution of language that dates back a now-extinct Middle English word, “wynnot.” Back then, “wyn” was a common spelling variant of “will,” so “wynnot” simply meant “will not.” By the 15th century, “wynnot” was replaced with “wonnot,” a blend of “woll” and “not.” The word “woll” itself was another spelling variation of “will” used in late Middle English until the 16th century.

By the 17th century, “wonnot” had been shortened to “wo’not,” and finally, by the 18th century, it settled into the modern form we know today: “won’t.” It remains the only common English contraction to preserve an archaic form. Linguists believe that “won’t” stuck around for a simple reason: It’s easier to pronounce than “willn’t.” After all, “Willn’t you be my neighbor?” just doesn’t have quite the same ring to it.