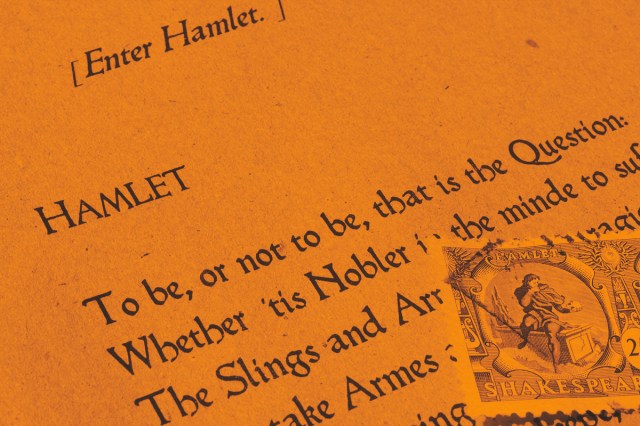

“Oh, I die, Horatio” is a memorable line from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, but not just for its drama. For contemporary readers, the verb “die” feels starkly out of place. In modern English, we’d expect “I am dying, Horatio.” The difference lies in a lesser-known yet essential part of a verb’s tense: the aspect.

When it comes to how a verb is presented, the tense will be past, present, or future — but that’s only part of the grammatical picture. The verb’s aspect reveals how the action unfolds over time. There are four main verb aspects in English, each existing in present, past, and future tenses:

- Simple: an action occurring at a specific time; general or habitual (“I paint,” “I painted,” “I will paint”)

- Progressive: an unfinished or ongoing action (“I am reading,” “I was reading,” “I will be reading”)

- Perfect: a finished action (“I have hiked,” “I had hiked,” “I will have hiked”)

- Perfect progressive: an action that was in progress but was then finished or is still happening (“I have been cooking,” “I had been cooking,” “I will have been cooking”)

The most versatile aspect is “simple”: “I die, Horatio.” In Shakespeare’s time, the simple aspect denoted present-tense action. But it sounds funny to us today because now simple verb aspects describe habitual actions (“I bake” or “I painted watercolors when I was younger”), general truths (“I hike on the weekends”), or scheduled events (“I will paint at the studio on Monday nights”). This aspect has the most variety of them all.

Other languages treat aspect differently. For example, in the Mokilese language of Micronesia, aspect is shown by the repetition of the verb:

- Rik sakai = “to gather stones” (rik is the verb for “to gather/collect”)

- Rik rik sakai = “to be gathering stones”

- Rik rik rik sakai = “to keep gathering stones”

If English worked that way, “I have been reading all weekend” might become: “I read read read all weekend.” Straightforward or more confusing? You decide.