Picture this: It’s Friday night and your plans include eating pizza while binge-watching Netflix (same!). Not only are these stellar plans, but you’ve also used not one but two gerund phrases. A gerund will always end in “-ing,” but it must fit some other requirements. It’s based on a verb, so it expresses an action or a state of being, but it functions as a noun. From grade school, we know that nouns are people, places, things, or ideas, but in grammar, they perform specific functions. In a sentence, they might be a subject, direct object, subject complement, or object of preposition. So if you spot an “-ing” verb that looks like it’s performing one of those jobs, it’s a gerund. In the above example, “eating” and “binge-watching” are subject complements of “plans.” Let’s look at some of the most common usages of gerunds.

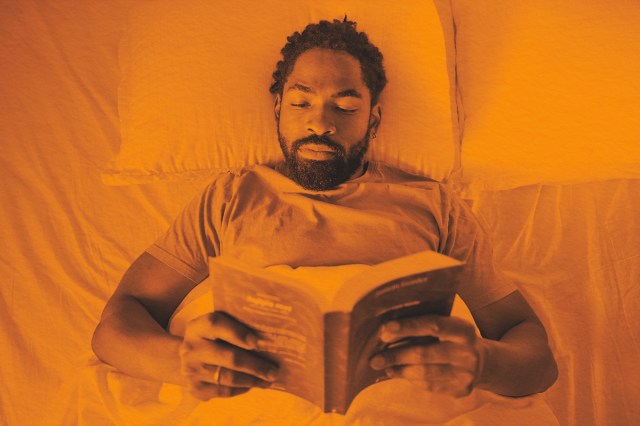

Many times, gerunds are the subject of the sentence, as in, “Running is a healthy hobby.” While “running” is traditionally a verb, in this case, it’s moonlighting as a noun. (The verb “is” works as a linking verb.) Gerund phrases are formed when a gerund has modifiers or objects related to it. For example, “Reading books is the best way to spend a rainy day” features the gerund phrase “reading books.” Here, the gerund is “reading” (a verb acting as a noun), the object of the gerund is “books,” and the verb is “is.”

Gerunds are also commonly found as the direct object of a verb (the thing being acted upon). Consider the sentence, “I enjoy baking cookies.” Here, “enjoy” is the verb, and “baking” is a gerund — it acts as a noun and is the direct object of “baking.” So, “baking cookies” is a gerund phrase.

But wait — why is it called a “gerund”? This word comes from the Latin gerundum, meaning “to be carried out.” In English, it’s used to refer to those shapeshifting “-ing” verbs that act as nouns, marking thousands of years of grammar evolution.