The ability to communicate via written language is one of the main behaviors that distinguish humans from other animals. In prehistoric times, three main writing systems developed independently — in the Near East, China, and Mesoamerica. Each of these systems evolved from pictography to a syllabary (symbols representing syllables) to an alphabet. The Latin alphabet we use today developed out of the Near East writing system. Along with the alphabet came specific forms of writing styles, each adapted to solve specific problems — whether increasing writing speed, improving legibility, or simply making the written word more beautiful.

Here we take a look back through the history of cursive handwriting and how different methods have emerged over time, from the elegant loops of medieval scribes to the standardized methods taught in modern classrooms.

Long before the printing press was invented, ancient Romans relied on handwriting for all written communication, records, and daily scribblings. Apart from the square capitals (capitalis quadrata) used for inscriptions on public monuments, the writing can be divided into two varieties: old and new Roman cursive. The word “cursive” comes from the Latin “currere,” meaning “to run,” signifying the letters ran together. Old Roman cursive, used from approximately the first century BCE to the third century CE, was a majuscule script — one that used capital-like letters, all of a similar height. In the late third century, old Roman cursive was largely replaced by new Roman cursive, which incorporated minuscule letters similar to the lowercase letters used today in the Latin alphabet. New Roman cursive became the dominant form of writing in ancient Rome, leading indirectly to Carolingian minuscule — and eventually to the script commonly used today.

Carolingian minuscule emerged during the eighth century, when several monasteries in the Carolingian realms of Northern France and Germany began developing scripts in an attempt to bring some clarity, order, and consistency to the swathe of barely legible cursives that had developed from the late-Roman period. The Carolingian ruler Charlemagne, keen on bringing about an intellectual revival, tasked the Anglo-Latin cleric Alcuin with standardizing texts across the empire as part of the broader educational reforms of the Carolingian Renaissance. Based primarily at the scriptorium (a collection of manuscripts) in Tours, France, Alcuin carried out his task with aplomb. The newly standardized script, with its clear, rounded letterforms, uniform heights, and consistent letter spacing, was ideal for copying manuscripts, and soon became the principal script in the empire’s scriptoria. By the end of the ninth century, Carolingian minuscule had emerged as the standard form of handwriting throughout most of Europe. It would influence virtually all subsequent Western scripts.

Gothic scripts emerged in the 12th century to meet the growing demand for legible religious texts. At the same time, the rise of universities saw an increased demand for costly parchment — the dense, angular nature of Gothic cursive conserved space on the page, while also creating a visually striking aesthetic that came to define medieval manuscripts. (Due to its dense, heavy, dark style, Gothic script is also known as blackletter.) Multiple variations existed across Europe, including the rigorous and formal littera textualis, and a rounder style known as rotunda, used in southern Europe. While beautiful and space-efficient, Gothic cursive’s density made it challenging to read, especially for those unfamiliar with the style. Despite this, it remained the dominant script for formal documents, religious texts, and legal records throughout the late Middle Ages.

Italic script emerged during the Italian Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries, primarily as a response to the cramped and illegible lettering of medieval Gothic cursive. Humanist scholars sought to revive what they believed were ancient Roman writing styles, but they actually based their new italic script primarily on Carolingian minuscule, which they mistakenly thought was Roman rather than medieval. Italic featured slanted, elegant letters with a flowing rhythm, combining speed with beauty. And unlike Gothic’s angular compression, italic spread letters horizontally with generous spacing, making texts easier to read. Italic’s tilt also made it cost-efficient, as copyists were able to fit more words on fewer pages, further promoting its spread across Europe.

Copperplate script, also called English roundhand, dominated formal writing from the 17th through 19th centuries. It first emerged in England, largely due to a need for an efficient commercial cursive style. During this time, metal engraving became more common and accessible, and scribes began working alongside engravers to recreate their work on copper plates for printing — hence the name. The script itself is graceful and highly refined, using elegant letterforms with dramatic contrasts between thick downstrokes and thin upstrokes. Copperplate demanded excellent pen control, and writing masters created elaborate manuals displaying examples of the script. Copperplate soon became the standard for formal documents, invitations, certificates, and business correspondence in Britain, and from there spread throughout much of Europe and North America.

Spencerian script was developed by Platt Rogers Spencer in the United States during the 1840s. Spencer set out to create a form of cursive handwriting that could be written very quickly and legibly to aid in matters of business correspondence, and was also suitably elegant for personal letter writing. At first, Spencerian script can appear very similar to copperplate, but it does have a number of distinguishing features, including a lack of emphasis on shaded downstrokes on small letters, the use of only one broad downstroke on capitals, minuscules being considerably smaller than capitals, and the joins between letters tending to space them further apart. Its elegance rivaled copperplate but proved faster and more practical for everyday use. It caught on quickly, becoming the standardized form of cursive handwriting taught in American schools in the 1850s.

Austin Palmer revolutionized cursive in the late 1800s by developing a system specifically designed for business efficiency and ease of teaching. The Palmer Method streamlined the flourishes of Spencerian script, creating a simpler and faster system of writing. In 1894, he published The Palmer Method of Business Writing, designed primarily for use in business colleges. The book was adopted by public school systems across the United States and became the standard cursive instruction for decades. Its focus on efficiency over artistry reflected the Industrial Age’s values of productivity and standardization — and while the method lacked the visual beauty of copperplate or Spencerian, it successfully democratized cursive by making it accessible to millions of students. The Palmer Method was used through the 1950s — and in some places, into the 1980s — but eventually began to fall out of favor when educational standards changed.

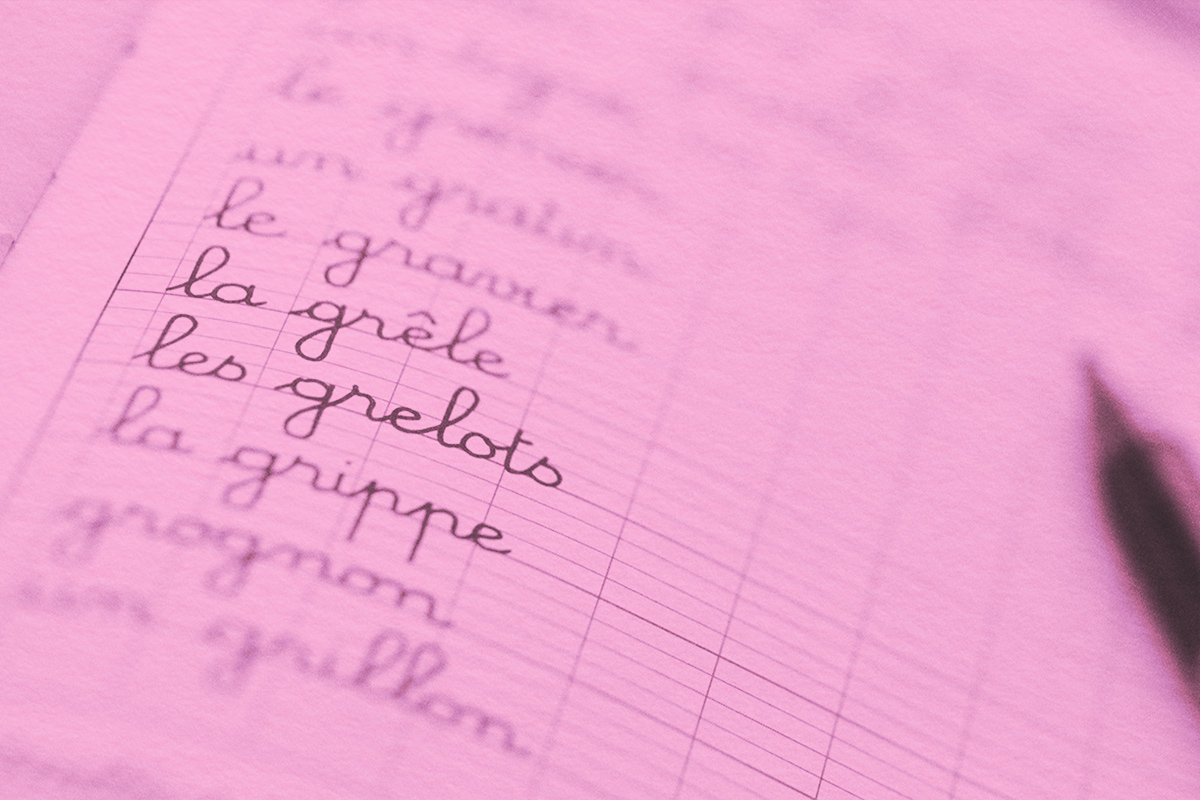

The Zaner-Bloser Method was adopted to teach handwriting in the latter half of the 20th century. It retains elements of the Palmer method, but it teaches block printing before teaching cursive script writing. In the early 21st century, some school districts dropped teaching cursive handwriting from the curriculum, but it’s now being added back. As of 2024, 24 states have a requirement to teach some kind of cursive handwriting in schools.